|

|

AbstractA 67-year-old female with no underlying diseases presented to the emergency department with dyspnea and fever. Laboratory findings were remarkable for pancytopenia, neutropenia, and a positive lupus anticoagulant, a marker of antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). Physical examination revealed necrosis involving the distal portions of the right index and middle fingers, the entire epiglottis, and the right hypopharynx. Imaging studies showed enterocolitis and multiple splenic infarcts. Subsequent evaluation demonstrated cerebellar infarcts and multiple ulcerative lesions in the colon. These symptoms were attributed to thromboembolism, leading to a diagnosis of APS and prompting the initiation of anticoagulant therapy. The hypopharyngeal necrosis resulted in a pharyngocutaneous fistula, which was managed with endoluminal vacuum-assisted closure therapy. Secondary wound healing was then promoted through laser cauterization of the reduced defect area. One month after the surgery, complete healing of the hypopharyngeal defect was achieved.

IntroductionAntiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is a systemic autoimmune disorder characterized by persistently elevated antiphospholipid antibodies, which can lead to recurrent thromboembolic events and repeated miscarriages [1,2]. For a diagnosis of APS to be established, there must be at least one event of thrombosis or miscarriage, along with two positive antiphospholipid antibody tests at least 12 weeks apart [3]. When thromboembolism associated with antiphospholipid antibodies occurs in three or more organs, it is defined as catastrophic APS, a rare and life-threatening condition [4]. According to a systematic review of the literature on APS [5], hematological abnormalities such as thrombocytopenia and pancytopenia are the most common symptoms, and peripheral thrombosis represents the most frequently reported thromboembolic complication, followed by stroke or transient ischemic attack, pulmonary embolism, and recurrent miscarriages. In cases of peripheral thrombosis, the most commonly affected sites are the distal upper or lower extremities; however, thrombosis of the inferior vena cava, subclavian vein, and testiclesŌĆöas well as penile infarctionŌĆöhas also been reported [5].

The present study reports the application of endoluminal vacuum-assisted closure (EndoVAC) for the successful treatment of a pharyngocutaneous fistula resulting from necrosis of the larynx and pharynx in a patient with APS.

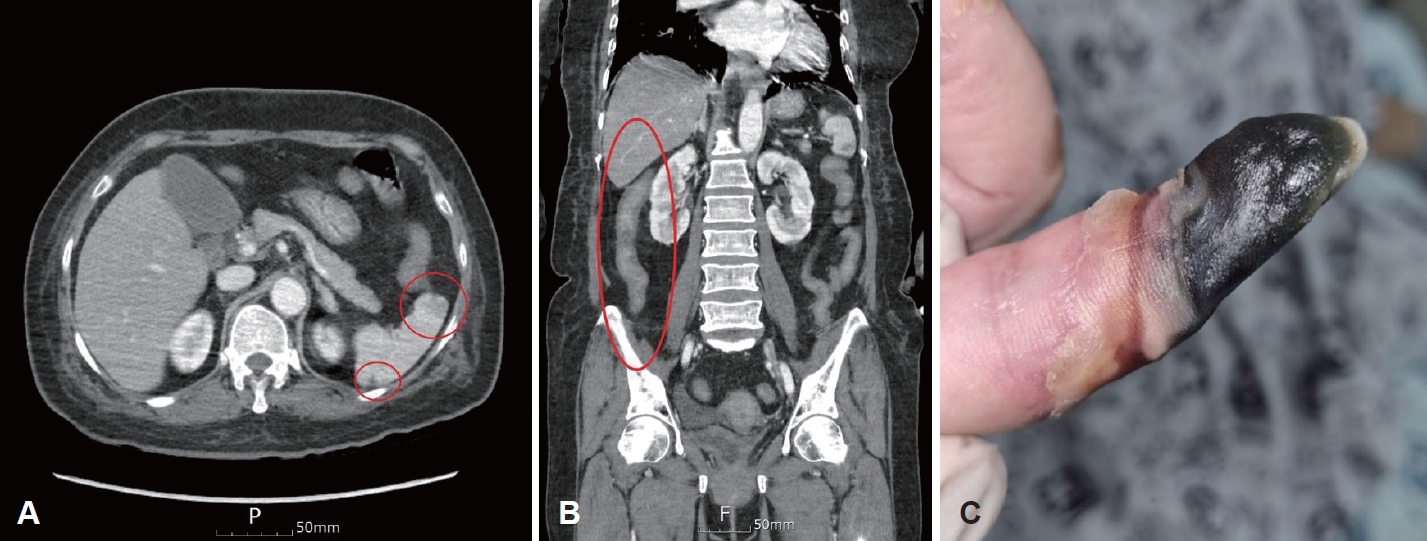

CaseA 67-year-old female with no underlying diseases presented to the emergency department with dyspnea and fever. She had recently visited Shanghai, China, and Phuket, Thailand, and had been diagnosed with influenza B and initiated on oseltamivir 2 days prior to her visit. Laboratory tests revealed pancytopenia and neutropenia, with a white blood cell count of 200 cells/╬╝L, neutrophils at 10 cells/╬╝L, hemoglobin at 10.9 g/dL, and platelets at 99000 cells/╬╝L. C-reactive protein was markedly elevated at 38.34 mg/dL, and creatinine was 1.89 mg/dL, suggesting acute inflammation and acute kidney injury, respectively. After resolution of the acute kidney injury, CT imaging revealed supraglottic region inflammation, interstitial pneumonia, multiple splenic infarcts, enterocolitis involving the ascending colon and terminal ileum, and necrosis of the distal portions of the right index and middle fingers (Fig. 1). An electrocardiogram confirmed atrial fibrillation, and multiple symptoms consistent with thromboembolismŌĆöincluding splenic infarction and finger necrosisŌĆöwere observed. A transthoracic echocardiogram was performed to check for the presence of cardiac thrombi, demonstrating normal cardiac function with no evidence of thrombi. Extensive blood tests were conducted to identify the causes of fever, pancytopenia, and multiple peripheral thromboses. The results showed a strongly positive lupus anticoagulant (2.10; reference range, 0-1.2 ratio), and the patient tested negative for 18 respiratory viruses, tuberculosis, antinuclear antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, extractable nuclear antigen antibodies, Leptospira, Hantaan virus, scrub typhus, and severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome. Therefore, the medical team diagnosed the patient with APS and initiated anticoagulant therapy.

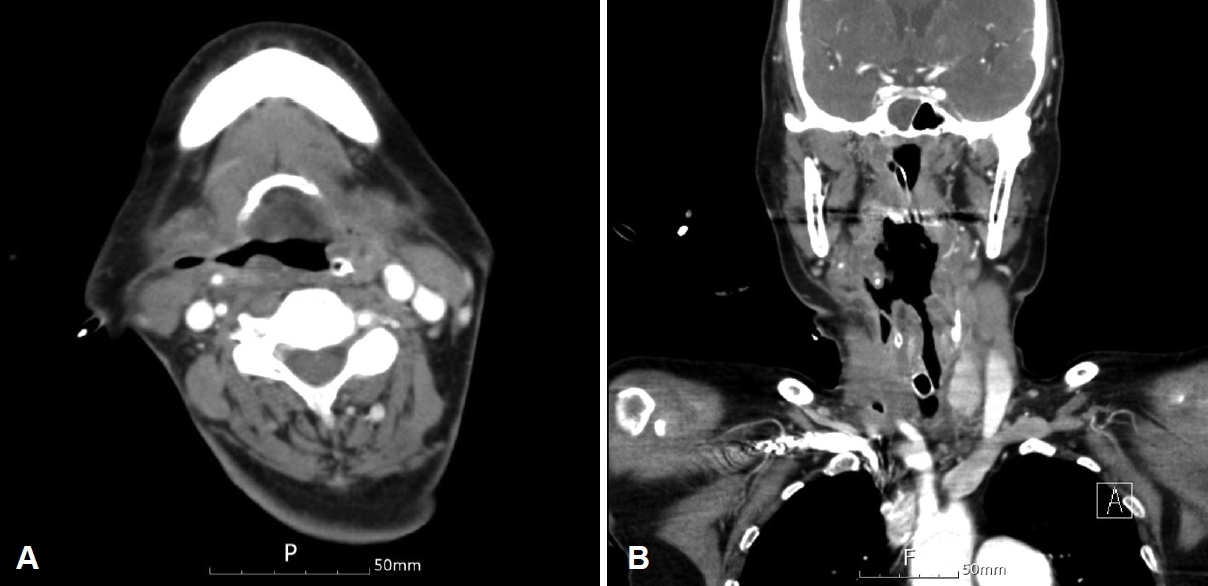

Three days after admission, the patientŌĆÖs dyspnea worsened, necessitating intubation. Subsequent extubation attempts failed, leading to a tracheostomy 1 week later. Flexible laryngoscopy immediately after the tracheostomy revealed necrosis of the epiglottis and right pharyngeal wall (Fig. 2A). Histopathological examination of the epiglottis showed a negative polymerase chain reaction test for Mycobacterium tuberculosis result, confirming acute necrotizing chondritis. Three weeks later, the epiglottis had completely disintegrated (Fig. 2B). Neck CT imaging indicated necrosis of the right hypopharyngeal wall (Fig. 3) and revealed a pharyngocutaneous fistula connected to the tracheostomy site. The patient also developed significant hematochezia and therefore underwent a colonoscopy, which revealed multiple ulcerative lesionsŌĆöincluding a deep ulcer measuring approximately 25 mmŌĆöin the terminal ileum and ascending colon (Fig. 4). These lesions were then treated with endoscopic epinephrine injection for hemostasis. Two days later, the patient complained of a headache. MRI of the brain showed an acute infarct in the right cerebellar hemisphere and subacute infarcts in the left cerebellar hemisphere and basal ganglia. Based on these comprehensive findings, the medical team of our hospital reached a diagnosis of catastrophic APS and attributed the observed necrosis of the epiglottis and hypopharynx to thromboembolism associated with this condition.

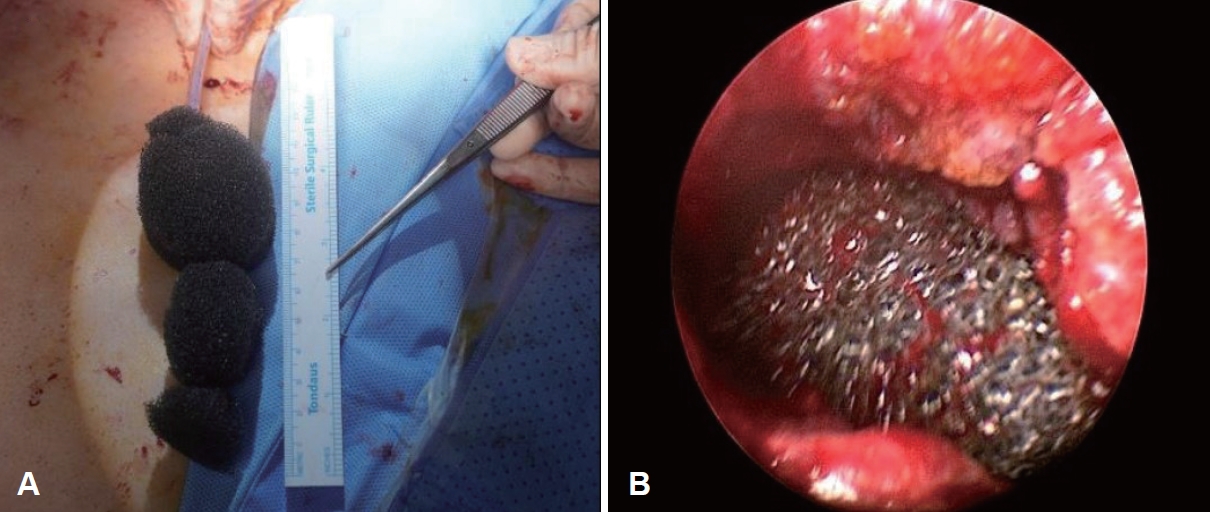

To treat the pharyngocutaenous fistula, we opted for the EndoVAC approach. Under general anesthesia, a hydrophilic foam dressing (V.A.C. Granufoam Dressing; KCI Manufacturing) was cut to size, attached to a Levin tube, and then inserted endoluminally from the oropharynx to the esophageal opening to cover the defect area (Fig. 5). After the procedure, the Levin tube was connected to a wall-mounted suction device in the patientŌĆÖs room to maintain continuous negative pressure. Ten days later, the EndoVAC sponge was removed under general anesthesia, and a slight reduction in the size and depth of the pharyngeal defect was observed (Fig. 6). A fresh EndoVAC assembly was then reinserted using the same technique. This process was repeated three additional times at intervals of 7 to 10 days. After a total of five EndoVAC treatments, the pharyngeal defect was confirmed to have sufficiently reduced. During the sixth procedure, instead of EndoVAC sponge reinsertion, laser cauterization was performed on the defect area and its surrounding tissue to promote secondary healing. One month later, flexible laryngoscopy revealed resolution of both the defect in the right pharyngeal wall (Fig. 7) and the connection to the tracheostomy site. A subsequent pharyngoesophagography showed mild aspiration but no evidence of the pharyngocutaneous fistula. The patient then recommenced oral intake, underwent tracheostomy decannulation, and has maintained a good recovery to date. This case study was approved by a certified Institutional Review Board (No. CNUHH-2024-200).

DiscussionWhile a few cases of epiglottis necrosis due to necrotizing supraglottitis have been reported [6-8], cases similar to the one presented hereinŌĆöfeaturing necrosis of the pharyngeal wall and the entire epiglottis without accompanying necrotizing supraglottitis or necrotizing deep neck infectionŌĆöare exceedingly rare in the literature. This case is likely indicative of vascular necrosis due to thromboembolism in the pharynx and larynx as a manifestation of APS.

Among the thromboembolic complications associated with APS, peripheral thrombosis is the most common, followed by stroke or transient ischemic attacks, pulmonary embolism, and recurrent miscarriages [5]. Thromboembolism can lead to damage to or necrosis of various organs, including the small intestine, skin, and kidneys, as documented in numerous studies and case reports [1,9-11].

In this case, the patient exhibited strongly positive antiphospholipid antibodies, along with thrombocytopenia, pancytopenia, acute kidney injury, spleen infarction, distal digital necrosis, intestinal necrosis, and cerebellar infarction. Because of the involvement of three or more organs, the condition was diagnosed as catastrophic APS, and anticoagulant therapy was promptly initiated.

We implemented EndoVAC therapy to address the pharyngocutaneous fistula caused by pharyngeal necrosis. Management of pharyngocutaneous fistulas can be categorized into conservative therapies, such as treatment with antibiotics and pressure dressings until the defect heals, and surgical interventions, such as primary closure or flap reconstruction [12]. In this case, since the size of the pharyngeal defect was approximately 1.5 cm, surgical interventions were deemed overly invasive and potentially costly, time-consuming, resource-intensive, and associated with postoperative complications, thus negatively impacting the patientŌĆÖs quality of life. Additionally, given the absence of prior radiation therapy, secondary wound healing was considered achievable. However, owing to ongoing irritation from oral secretions, such as saliva, conservative measures were considered likely insufficient for proper healing. As a result, it was decided to proceed with EndoVAC therapy.

The advantages of EndoVAC therapy are twofold. First, it effectively prevents oral contents, such as saliva, from directly or indirectly contacting the defect site. Second, it increases blood flow around the wound, which enhances the supply of oxygen and nutrients while promoting the removal of waste products, thus aiding in secondary wound healing [13]. In this context, Chen, et al. [14] have demonstrated that vacuum-assisted wound dressing in the ears of white rabbits promotes angiogenesis and endothelial cell proliferation, thereby improving blood flow in the wound area.

A limitation of treatment in this case was that the defect site was located in the hypopharynx, making it difficult to place the sponge appropriately under local anesthesia; thus, general anesthesia was required for each EndoVAC sponge replacement. For patients in poor overall health, enduring repeated general anesthesia could be challenging. The recommended time interval between EndoVAC sponge changes is 7 to 10 days, as prolonged placement of the sponge may lead to tissue adhesion and potential obstruction of the connecting tube by exudate, which could in turn compromise negative pressure [15].

NotesAuthor contributions Conceptualization: Joon Kyoo Lee. Data curation: Hye-Bin Jang, In Seok Kang, Hyeong Seok Lee. Formal analysis: Joon Kyoo Lee. Investigation: Hye-Bin Jang, Hyeong Seok Lee. Methodology: Joon Kyoo Lee. Resources: Hye-Bin Jang. Supervision: Joon Kyoo Lee. Validation: Joon Kyoo Lee. Visualization: Hye-Bin Jang, In Seok Kang, Hyeong Seok Lee. WritingŌĆöoriginal draft: Hye-Bin Jang. WritingŌĆöreview & editing: Joon Kyoo Lee. Fig.┬Ā1.Findings at admission, suggestive of thromboembolism. A: Multiple splenic infarcts, characterized by hypoattenuating areas within the spleen. B: Enterocolitis involving the ascending colon and terminal ileum. C: Necrosis of the distal phalanx of the right index finger.

Fig.┬Ā2.Flexible laryngoscopy findings. A: Necrosis of the epiglottis with generalized whitish tissue changes, observed immediately after tracheostomy. B: Complete breakdown of the epiglottis, observed 3 weeks later.

Fig.┬Ā3.Neck CT demonstrating necrosis of the right lateral pharyngeal wall and the formation of a pharyngocutaneous fistula to the tracheostoma. A: Axial view. B: Coronal view.

Fig.┬Ā4.Colonoscopy demonstrating multiple hemicircumferential ulcerative lesions in the terminal ileum and ascending colon.

Fig.┬Ā5.Endoluminal vacuum-assisted closure therapy procedure. A: A Levin tube is inserted through the nose and passed out through the mouth. The perforated distal end of the tube is then cut off. After a hydrophilic sponge is customized with a central narrow space, the Levin tube is attached almost to the end of the sponge and secured. B: The sponge is then inserted through the mouth and is positioned using laryngoscopy within the pharynx at the defect site.

REFERENCES1. Abernethy ML, McGuinn JL, Callen JP. Widespread cutaneous necrosis as the initial manifestation of the antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. J Rheumatol 1995;22(7):1380-3.

2. Garcia D, Erkan D. Diagnosis and management of the antiphospholipid syndrome. N Engl J Med 2018;378(21):2010-21.

3. Pengo V, Denas G, Padayattil SJ, Zoppellaro G, Bison E, Banzato A, et al. Diagnosis and therapy of antiphospholipid syndrome. Pol Arch Med Wewn 2015;125(9):672-7.

4. Carmi O, Berla M, Shoenfeld Y, Levy Y. Diagnosis and management of catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome. Expert Rev Hematol 2017;10(4):365-74.

5. Abdel-Wahab N, Lopez-Olivo MA, Pinto-Patarroyo GP, Suarez-Almazor ME. Systematic review of case reports of antiphospholipid syndrome following infection. Lupus 2016;25(14):1520-31.

6. Klcova J, Mathankumara S, Morar P, Belloso A. A rare case of necrotising epiglottitis. J Surg Case Rep 2011;2011(2):5.

7. Villemure-Poliquin N, Ch├®nard-Roy J, Lachance S, Leclerc JE, Lemaire-Lambert A. Necrotizing epiglottitis with necrotizing fasciitis in a child: a case report and review of literature. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2020;138:110385.

8. Richardson C, Muthukrishnan PT, Hamill C, Krishnan V, Johnson F. Necrotizing epiglottitis treated with early surgical debridement: a case report. Am J Otolaryngol 2018;39(6):785-7.

9. Christiansen TK, Nilsson AC, Madsen GI, Voss A. Small intestine necrosis in catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome: a rare and severe case. Lupus 2022;31(6):754-8.

10. C├│rdoba-Fern├Īndez A, Marmol-Garc├Ła F, C├│rdoba-Jim├®nez VE. Hallux partial necrosis associated with antiphospholipid syndrome: the importance of early accurate diagnosis. Life (Basel) 2023;13(4):1009.

11. Espinosa G, Rodr├Łguez-Pint├│ I, Cervera R. Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome: an update. Panminerva Med 2017;59(3):254-68.

12. Busoni M, Deganello A, Gallo O. Pharyngocutaneous fistula following total laryngectomy: analysis of risk factors, prognosis and treatment modalities. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 2015;35(6):400-5.

13. Morris GS, Brueilly KE, Hanzelka H. Negative pressure wound therapy achieved by vacuum-assisted closure: evaluating the assumptions. Ostomy Wound Manage 2007;53(1):52-7.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|