|

|

AbstractMyxomas are benign mesenchymal tumors that rarely occur in the head and neck. When they occur in the head and neck region, they are mostly involved in the mandible and maxilla areas. Myxomas arising from subcutaneous soft tissues of the external auditory canal (EAC) are very rare. We present a case of a 78-year-old female patient who had been suffering from leftsided hearing disturbance for 6 months. The otoscopic examination revealed a round mass arising from the anterior and superior wall of EAC, almost completely filling the EAC and partially invading the outer layer of the tympanic membrane. This mass was completely resected via microscopic excision and tympanoplasty, and the following histopathological examination revealed the mass to be consistent with a myxoma. Unfortunately, a myxoma reappeared at the superior wall of the auditory canal, 6 months after the surgery. The patient is currently being managed with monthly marsupialization without reoperation.

IntroductionLesions of the external auditory canal (EAC) include tumors such as osteomas, exostosis, cholesteatomas, hemangiomas, and keratosis obturans. Although these are more commonly encountered, myxoma—an exceedingly rare benign mesenchymal tumor—is seldom found in the EAC, with only a few cases reported in the literature [1]. Management of myxomas in the head and neck region is particularly challenging, as anatomical complexity and the presence of vital structures within a confined space make complete surgical excision of the mass difficult. In such cases, alternative therapeutic strategies may need to be considered.

This report presents a rare case of EAC myxoma in a 78-year-old female with a chief complaint of hearing loss. After initial surgical excision and subsequent recurrence, the patient was managed with monthly marsupialization. This case provides valuable insights into the diagnosis and management of myxoma in the EAC, highlighting the differential diagnosis from other EAC tumors and unique features of the lesion.

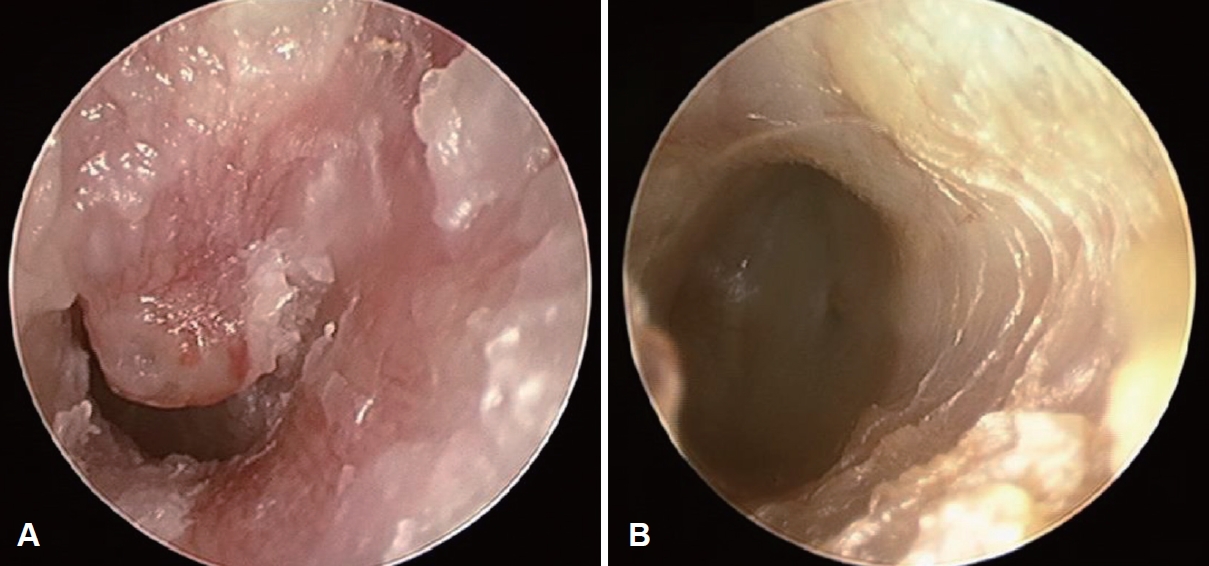

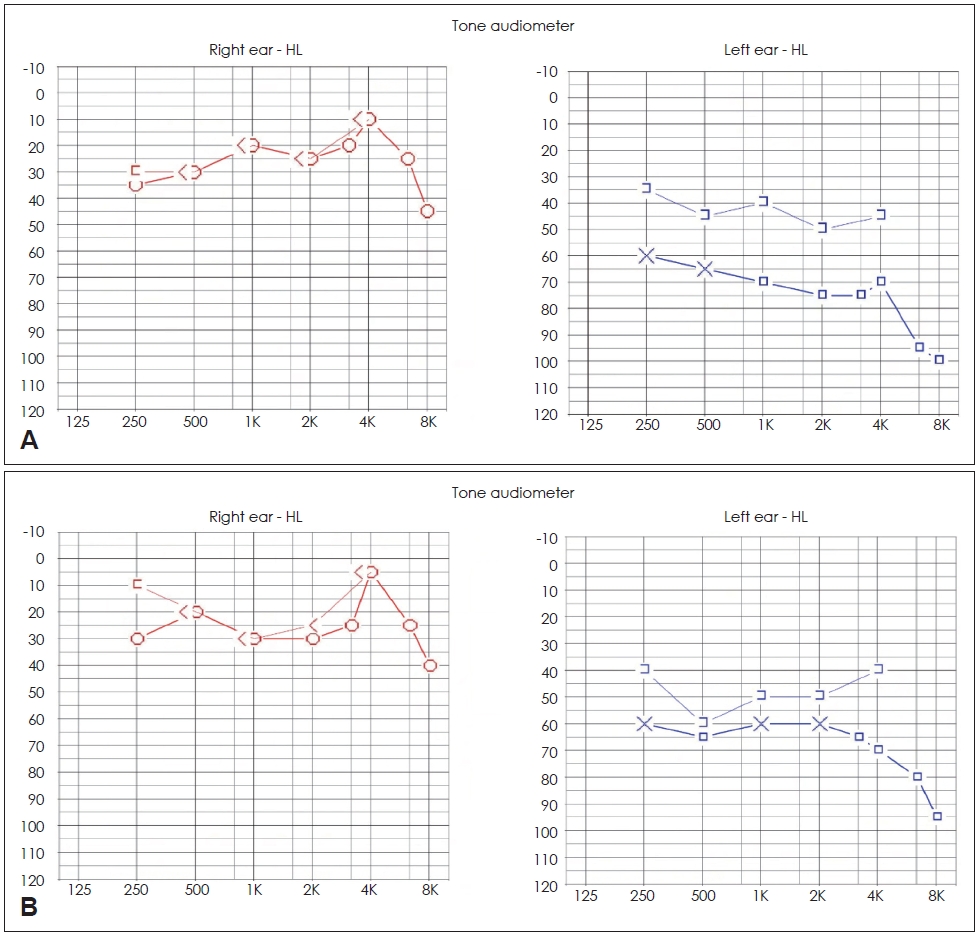

CaseThe subject of this case, a 78-year-old female patient with a history of hypertension, cholecystectomy visited the outpatient department with the main complaint of hearing loss on the left side that started 6 months ago. She did not complain of otalgia. Otoscopic examination revealed a reddish round mass originating from the anterior and superior walls of the EAC, causing nearly complete occlusion (Fig. 1A). Pure tone audiometry performed at the initial outpatient visit showed moderate to severe mixed hearing loss on the left side (Fig. 2A).

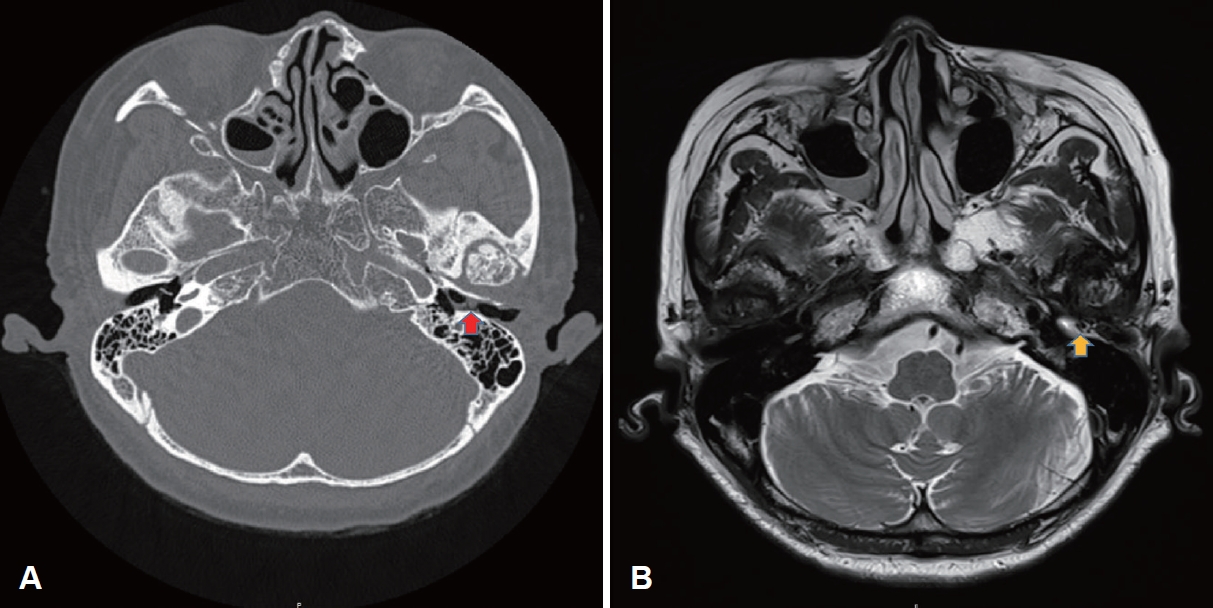

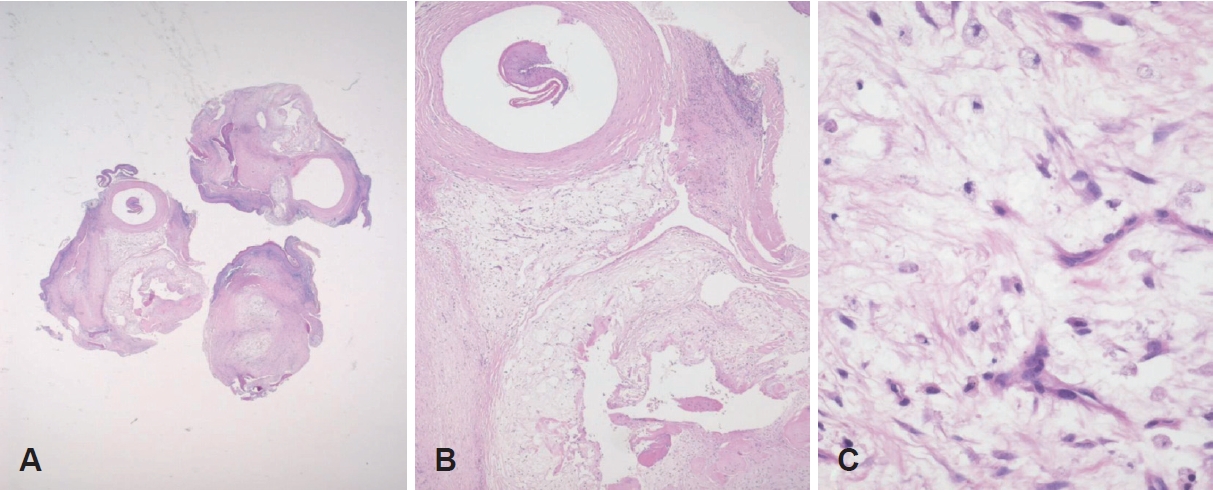

For the initial treatment of the subject, 3rd-generation cephalosporin antibiotics and low-dose steroids were used for 2 weeks, with suspicion of an inflammatory polyp. Cholesteatoma could not be ruled out as temporal bone CT showed an 8 mm iso-dense mass and diffusion restriction in the diffusion- weighted image (DWI) of the temporal bone MRI (Fig. 3). However, as the mass grew over the weeks, an excisional microscopic biopsy was planned via a post-auricular approach. Although performing a biopsy in the outpatient clinic was considered prior to surgery, it was presumed challenging to obtain an adequate tissue sample due to the soft and pliable texture of the mass and its proximity to the tympanic membrane (TM). Moreover, given that definitive symptom relief would require complete excision regardless of the tumor type, and also considering the patient’s personal difficulty in making frequent outpatient appointments, prompt surgical intervention was chosen to minimize the number of hospital visits. During surgery, a poorly marginated mass with a broad pedicle in the EAC anterior and superior walls, partially invading the outer layer of the TM, was observed. Tympanomeatal flap elevation was performed, and the outer and middle layers of the TMs were separated with a round knife. The mass was resected en-bloc with the EAC skin and part of the outer layer of the TM using microscissors. The autologous temporalis fascia was inserted over the middle layer of the TM, covering bare bone in an overlay method for reconstruction. The histopathological finding of the resected mass was consistent with myxoma, as the lesion was composed of spindle-shaped cells lying in a loose-textured, well-vascularized myxoid stroma (Fig. 4).

To rule out Carney syndrome, a thorough physical examination was performed. No dermatological findings, such as spotty skin pigmentation, were observed. The patient had a history of cholecystectomy and transient liver enzyme elevation, but preoperative abdominal CT did not reveal any abnormalities. Previous screening breast sonography and an echocardiogram also showed no evidence of breast or cardiac myxoma. Therefore, this case was concluded to be a localized, primary myxoma of the EAC, with no evidence of systemic involvement.

After surgery, the neo-TM and EAC returned to normal, with pure tone audiometry showing a reduction in the air-bone gap (Figs. 1B and 2B). Unfortunately, the myxoma lesion reappeared 6 months after the surgery during the follow-up. As the patient did not want to be re-operated considering her old age, she is currently being managed with a monthly marsupialization in the outpatient clinic. As conductive hearing loss was the only symptom caused by the myxoma, regular marsupialization of the mucoid contents of the tumor could effectively alleviate the patient’s complaint.

DiscussionMyxoma is a benign mesenchymal tumor typically found in the antrum of the heart. It rarely occurs in the head and neck regions. Most myxomas in the head and neck regions involve the mandible and maxilla areas, but may also arise from different parts of the temporal bone, such as the ear lobule, middle ear, and very rarely the EAC [2]. Given that myxomas are a hallmark feature of Carney complex (CNC) syndrome, it is crucial to consider this syndrome in the differential diagnosis when a myxoma is identified. The constellation of symptoms in CNC includes four major criteria: 1) spotty skin pigmentation (such as pigmented lentigines and blue nevi on the face, neck, and trunk), 2) endocrine tumors (primarily primary pigmented nodular adrenocortical disease, and less commonly, pituitary, thyroid, and growth hormone-secreting tumors), 3) myxomas (e.g., cardiac, breast, osteochondromyxomas, and cutaneous/mucosal types), and 4) non-endocrine tumors (including psammomatous melanotic schwannomas, breast ductal adenomas, and large cell calcifying Sertoli cell tumors of the testis) [2]. A diagnosis of CNC is made when two or more characteristic clinical features are present, or when one major criterion is identified in conjunction with either a pathogenic PRKAR1A gene mutation or a first-degree relative with confirmed CNC. Therefore, when myxoma is diagnosed, a thorough evaluation, including an echocardiogram, skin examinations, laboratory tests for endocrinopathy, and screenings for both endocrine and non-endocrine tumors, is typically required [2,3].

Among the mass-like lesions occurring in the EAC, those that require diagnostic differentiation from myxoma include osteoma, exostoses, hemangioma, keratosis obturans, and EAC cholesteatoma [4]. The various characteristics of EAC tumors are summarized in Table 1.

Osteoma is a unilateral, pedunculated bony tumor associated with earwax, debris, or secondary cholesteatoma, whereas exostoses are broad-based osseous overgrowths in the medial bony EAC, which usually occur bilaterally [4,5]. These first two disease entities can be differentiated from myxoma in that they are hard, well-marginated lesions, unlike myxoma. Hemangioma is a congenital growth of extra blood vessels that usually invades the auricles and other areas of the face and neck. Although hemangiomas are soft, poorly marginated tumors similar to myxoma, hemangiomas are typically red glomerular masses, unlike the clear gelly-like features of myxoma. MRI is highly sensitive and specific for the diagnosis of hemangioma, with low signal intensity on T1-weighted image (WI) and high signal intensity on T2-WI [4].

Keratosis obturans may be confused with a tumor, but it is the accumulation of desquamated keratin plugs. It may occur bilaterally at a relatively young age, with symptoms of conductive hearing loss and ear pain. Although keratosis obturans is similar to myxoma in that it shows slight or no bone erosion, after exfoliation of the keratin material, severe redness and inflammation in the subepidermal layer of the skin in the EAC can be observed [6].

Unlike a simple inflammatory polyp, which is an acute condition, EAC cholesteatoma is a chronic inflammatory condition characterized by the proliferation of keratinizing squamous epithelium within the epithelial-lined canal of the EAC, leading to bony destruction. EAC cholesteatoma is frequently found on one side in relatively middle-aged and elderly individuals with normal hearing [7]. Whereas temporal bone CT is the method of choice to localize EAC cholesteatoma by confirming bony erosion or destruction, conventional MRI findings may be nonspecific. However, late enhancement of the lesion after 30 to 45 minutes from contrast administration may indicate cholesteatoma. The application of DWI in MRI is highly helpful, as cholesteatoma depicts high signal intensity due to diffusion restriction [8]. It is challenging to distinguish myxoma from cholesteatoma, as both appear with high intensity on T2-WI and either low or homogeneous intensity on T1-WI. They are also generally either hypodense or isodense in temporal bone CT [9]. The most significant difference is that cholesteatoma usually involves substantial bony erosion in CT, whereas myxoma rarely does. The differences in imaging features between EAC cholesteatoma and myxoma are shown in Table 2.

Most previously published studies on EAC myxomas report symptoms such as ear pain, a sensation of fullness, hearing loss, and intermittent otorrhea [3]. However, in contrast to these typical presentations, the patient in this case primarily complained of hearing loss without any accompanying pain, which was a distinct clinical manifestation compared to previous reports. Also, although the lesion in this case was located in the anterior portion of the EAC, which was consistent with prior reports, no evidence of bony erosion was observed in the CT, unlike previous reports [3].

The definite diagnosis of myxoma is confirmed through the histopathological examination. Histologically, a hypocellular composition of satellite or spindle cells with small, round to oval nuclei and scant cytoplasm is observed in the loose mucoid stroma. The stroma contains an acid mucopolysaccharide-rich myxoid matrix. Mitoses and cellular atypia are generally absent, supporting the benign nature of the tumor. Vascularization is minimal, and although the lesion is well-circumscribed, it is not encapsulated [10].

The treatment of choice for myxoma is complete surgical removal, and radiotherapy is not very successful [11]. The entire tumor must be resected with a clear margin to prevent a recurrence. The precise recurrence rate of myxoma in the EAC is unknown due to its extremely rare incidence; however, myxomas of the head and neck area are notorious for local recurrence [12]. The frequent recurrence is due to incomplete surgical resection, primarily because of the myxoma’s mucoid and gelatinous features and ill-defined margins [13]. The close proximity of vital anatomical structures further complicates the achievement of complete resection. When complete surgical resection is difficult, as in this case, marsupialization can be used as a palliative treatment for EAC myxomas, providing temporary symptomatic relief by draining the tumor and reducing its size. However, this approach has notable limitations, as the inability to achieve complete excision with this technique can leave a risk for tumor regrowth, long-term management challenges, and repeated procedures [3]. Furthermore, given the association between EAC myxoma and systemic syndromes like CNC, marsupialization alone may delay more comprehensive diagnosis and management [14,15].

Additionally, though rare, there is a risk that EAC myxomas could undergo malignant transformation over time. While myxomas are generally benign, with excellent long-term prognosis [16], there have been isolated reports of these tumors transitioning to a more aggressive, sarcomatous form [11]. Such malignant changes are extremely uncommon but underscore the importance of thorough long-term surveillance and complete surgical resection when feasible. Therefore, while repeated marsupialization may serve as an effective alternative to surgical excision for symptom relief, careful long-term monitoring is strongly recommended [3,11].

In conclusion, isolated myxomas of the EAC are extremely rare. Before suspecting a myxoma, it is essential to first perform a comprehensive differential diagnosis for various EAC lesions. When myxoma is confirmed histopathologically, Carney syndrome must be considered, for it may be a sign of serious and even fatal disease. Myxomas should be completely resected when possible, but since they are benign, noncancerous tumors, frequent marsupialization can serve as a palliative measure for symptom reduction when the patient refuses surgical treatment. However, from a long-term perspective, it is important to monitor for potential recurrence.

NotesAuthor Contribution Conceptualization: Jung Mee Park. Data curation: Jun Seop Kim, Sukjune Byun, Chang Heum Han. Formal analysis: Jung Mee Park. Investigation: all authors. Project administration: Jung Mee Park. Resources: Jung Mee Park. Supervision: Jung Mee Park. Visualization: Jun Seop Kim. Writing—original draft: Jun Seop Kim, Jung Mee Park. Writing—review & editing: all authors. Fig. 1.Otoscopic images of the lesion. A: Pre-operative otoscopic image shows a reddish, round mass occluding the left external auditory canal (EAC). B: Post-operative otoscopic image at 6 months shows a clear neotympanic membrane and EAC.

Fig. 2.Pure-tone audiometry of the patient. A: Pre-operative pure tone audiometry shows a moderate to severe mixed hearing loss on the left side. B: Post-operative pure tone audiometry shows a reduced air-bone gap.

Fig. 3.Radiological images of the lesion. A: Temporal bone CT. Soft tissue lesion in the left external auditory canal (EAC) with tympanic membrane (TM) thickening (red arrow) but without any bone lysis. B: Temporal bone MRI. 8 mm non-enhancing T2-weighted image hyperintense mass at left medial EAC, abutting to TM (yellow arrow).

Fig. 4.Pathological images of the lesion. A: Pathologic evaluation reveals a well-circumscribed mass with predominantly myxoid stroma and partly fibrocystic change (hematoxylin and eosin [H&E], ×10). B: Bland stellate- or spindle-shaped cells are scattered in the hypovascular myxoid matrix (H&E, ×100). C: Some muciphages are intermingled with thin strands of vessels (H&E, ×400).

Table 1.Differentiating diagnostic features of various EAC tumors Table 2.Image features among EAC cholesteatoma and myxoma REFERENCES1. Andrews T, Kountakis SE, Maillard AA. Myxomas of the head and neck. Am J Otolaryngol 2000;21(3):184-9.

2. Hasnaoui M, Masmoudi M, Belaid T, Mighri K. Isolated myxoma of the external auditory canal: a case report and literature review. Ear Nose Throat J 2021;100(10_suppl):991S-4.

3. Lee DH, Jeong SH, Kim H, Shin E. Isolated myxoma in the external auditory canal of a 10-year-old girl. J Int Adv Otol 2015;11(3):264-6.

4. Tsuno NSG, Tsuno MY, Coelho Neto CAF, Noujaim SE, Decnop M, Pacheco FT, et al. Imaging the external ear: practical approach to normal and pathologic conditions. Radiographics 2022;42(2):522-40.

5. Neumann M, Evans M, Sargent E. Internal auditory canal exostosis: a case report and review of literature. Otolaryngol Case Rep 2019;11:100119.

6. Shinnabe A, Hara M, Hasegawa M, Matsuzawa S, Kanazawa H, Yoshida N, et al. A comparison of patterns of disease extension in keratosis obturans and external auditory canal cholesteatoma. Otol Neurotol 2013;34(1):91-4.

7. Sy A, Regonne EJ, Missie MY, Ndiaye M. Cholesteatoma of external auditory canal: a case report. PAMJ Clin Med 2019;1:11.

8. Aswani Y, Varma R, Achuthan G. Spontaneous external auditory canal cholesteatoma in a young male: imaging findings and differential diagnoses. Indian J Radiol Imaging 2016;26(2):237-40.

9. Yu SH, Shim YS, Park SH, Choi SJ, Chung DH, Yoon SJ. MRI findings of renal myxoma: a case report and literature review. J Korean Soc Radiol 2022;83(1):162-7.

10. Hoshino T, Hamada N, Seki A, Ogawa H. Two cases of myxoma of the external auditory canal. Auris Nasus Larynx 2012;39(6):620-2.

11. Zhang L, Zhang M, Zhang J, Luo L, Xu Z, Li G, et al. Myxoma of the cranial base. Surg Neurol 2007;68(Suppl 2):S22-8.

12. Dutta S, Gure PK, Pal S, Saha S. Middle ear myxoma: a diagnostic dilemma and its management, a case report. Egypt J Otolaryngol 2018;34:351-4.

13. Charabi S, Engel P, Bonding P. Myxoid tumours in the temporal bone. J Laryngol Otol 1989;103(12):1206-9.

14. Ferreiro JA, Carney JA. Myxomas of the external ear and their significance. Am J Surg Pathol 1994;18(3):274-80.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|