|

|

AbstractBackground and ObjectivesHigh-speed videolaryngoscopy (HSV) is the most effective tool for visualizing vocal fold vibrations, offering superior image quality compared to laryngeal videostroboscopy (LVS). Digital kymography (DKG), derived from HSV, allows objective analysis of vibratory patterns, but lacks audio feedback, limiting its diagnostic utility. In contrast, LVS enables simultaneous audio-visual feedback, aiding in the diagnosis of functional voice disorders. To address this limitation, we developed an automated DKG system with synchronized voice playback and evaluated its diagnostic value.

Subjects and MethodWe enrolled 102 patients with various voice disorders, including muscle tension dysphonia (n=16), spasmodic dysphonia (n=15), vocal tremor (n=14), vocal fold palsy (n=12), presbyphonia (n=12), and others. We compared diagnostic accuracy among three conditions: conventional DKG, DKG with non-synchronized voice playback, and DKG with synchronized voice playback. Two otolaryngologists and one speech-language pathologist assessed intra- and inter-rater reliability.

IntroductionVarious techniques, including acoustic, aerodynamic, electroglottographic, and visual observation of the larynx, have been used to analyze voice physiology and pathology. Among these, visual inspection of the larynx is crucial for determining the cause of voice disorders [1]. However, because the vocal folds vibrate at 80-150 Hz in males and 180-250 Hz in females during normal speech [2-4], such oscillations cannot be directly observed. Thus, conventional laryngeal videoendoscopy has limited value in assessing vocal fold vibration, leading to the use of laryngeal videostroboscopy (LVS), high-speed videolaryngoscopy (HSV) [5], and videokymography (VKG) [6].

LVS is widely used in clinical practice, but it provides only morphological and subjective evaluation. It also fails in cases of severe aperiodicity or when phonation cannot be sustained. Patel, et al. [2] reported that LVS was not feasible in 100% of severe and 64% of moderate cases, with a final success rate of only 37% [5]. Despite these limitations, LVS allows immediate playback and simultaneous voice feedback, which explains its popularity. In contrast, HSV offers higher image quality and diagnostic accuracy than LVS [2,3,7,8], but its clinical use is restricted by long encoding times, large file sizes, frame-by-frame analysis, and lack of audio feedback.

To address these limitations, several post-processing functional imaging methods have been developed, including digital kymography (DKG) [9], glottal area waveform [10], glottal width waveform [11], kymographic edge detection [12], laryngotopography [13], phonovibrography [14], and two-dimensional DKG (2D DKG) [15]. Among these, DKG is considered the most effective for evaluating the temporal characteristics of HSV data, providing objective parameters such as symmetry, periodicity, open quotient (OQ), close quotient (CQ), and speed quotient (SQ) [16,17]. Introduced by Wittenberg in 1997 [9] and further described in 1999 [18], DKG allows quantitative assessment of vocal fold vibrations that are difficult to capture with frame-by-frame HSV analysis.

Voice disorders encompass a broad spectrum of etiologies, ranging from functional and neurologic conditions without overt structural changes to morphological or structural lesions of the vocal folds. Accurate diagnosis can therefore be challenging, particularly when clinicians rely solely on visual inspection of vocal fold vibration without auditory feedback.

This limitation is especially pronounced in functional voice disorders such as spasmodic dysphonia, tremor, and muscle tension dysphonia, where structural abnormalities are minimal or absent. In such cases, the ability to simultaneously observe vibratory irregularities and perceive the corresponding acoustic events is crucial for accurate diagnosis. Existing tools fail to fully meet this need: LVS provides audio-visual feedback but often fails in severely aperiodic or short phonation, while HSV offers detailed imaging but lacks synchronized auditory cues.

This gap represents an important unmet clinical need because there is currently no diagnostic tool that integrates the temporal resolution of HSV with the auditory information essential for clinical assessment. To address this, we developed an automated DKG system with synchronized voice playback, aiming to combine visual and auditory information into a single platform and thereby improve diagnostic accuracy for diverse voice disorders.

Subjects and MethodsParticipantsDetails of the participants are presented in Table 1. The study included patients with a wide spectrum of voice disorders, encompassing functional, neurologic, and morphological lesions such as muscle tension dysphonia, vocal fold palsy, tremor, spasmodic dysphonia, presbyphonia, nodules, polyps, cysts, and Reinke’s edema.

Among patients who visited to Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital, 102 patients with voice disorders diagnosed by laryngoscopy and pathological examination were registered (female=51, male=51). The distribution of age was 24 to 74 years for female, with an average age of 52.5 years, and 32 to 85 years old for male, with an average age of 62.8 years. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital (IRB No. 55-2023-050).

Details of the diagnostic categories are summarized in Table 1. Functional and neurologic disorders accounted for 67.6% of cases, whereas morphological or structural lesions accounted for 32.4%. The clinical diagnosis established at the time of otolaryngology consultation was regarded as the reference standard for subsequent analysis.

Instrumentation and procedureAn HSV system (USC-700MFC, U-medical) was used to assess vocal fold vibration. A 9.2 mm diameter, 70° rigid laryngoscope (8706 CA, Karl Storz), a zoom coupler (f=16-34 mm, MGB), and a 300-watt xenon light source (NOVA 300, Storz) were used for examination. Images were recorded at the rate of 1500-2000 frames per second, with a spatial resolution of 208×304 pixels. The total recording time was 10 s, and the total encoding time was less than 2 min. The size of the acquired image file was approximately 70 MB. The laryngoscope connected to HSV camera was inserted through the oral cavity to examine the vocal folds. All patients were instructed to phonate a sustained vowel /e/ or /i/ with a comfortable pitch for 3 s, followed by a high pitch for 2 s and a low pitch for 2 s. Subsequently, the patients were directed to produce 3 to 4 consecutive shouts. The patients’ voices were recorded simultaneously during the HSV examination. The microphone for voice recording was positioned approximately 10-15 cm away from the patient. Caution was exercised to avoid contact with the oral and oropharyngeal mucosa because the distal end of the laryngoscope was hot. After the HSV examination, a post-processing procedure was conducted to obtain a multi-line scanning DKG. We developed software for the automatic scrolling DKG with synchronized voice playback for the viewer program. Multi-slice DKG imaging consists of still image files in JPEG format, with the time information for each frame stored in a separate file. The DKG files in the JPEG format had a size of 30328×1880 pixels. Using this system, the maximum recording time is 10 s, and up to 10 scan lines can be displayed simultaneously.

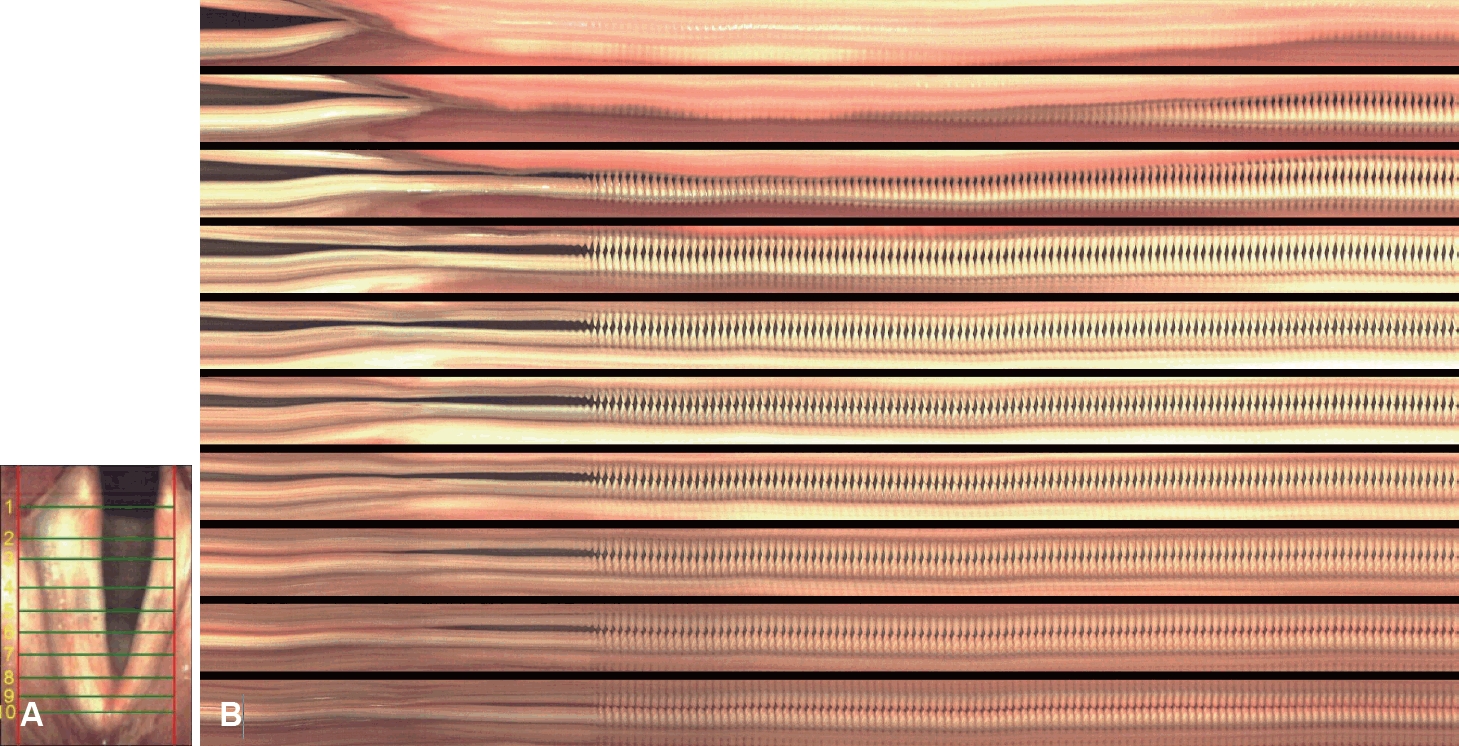

Implementation of automated DKG application with synchronized voice playbackTo generate a multi-slice digital kymograph, the obtained HSV image was loaded and 10 lines were drawn perpendicular to the glottal axis. Automatic scrolling of the DKG files made it possible to view all files within 10 s. At the same time, automated DKG with synchronized voice playback was implemented by dubbing the prerecorded waveform audio format (WAV) files. This software was developed as a Windows desktop application using C# language. The user interface of the developed automated DKG with synchronized voice playback is shown in Fig. 1 (Supplementary Videos 1-7).

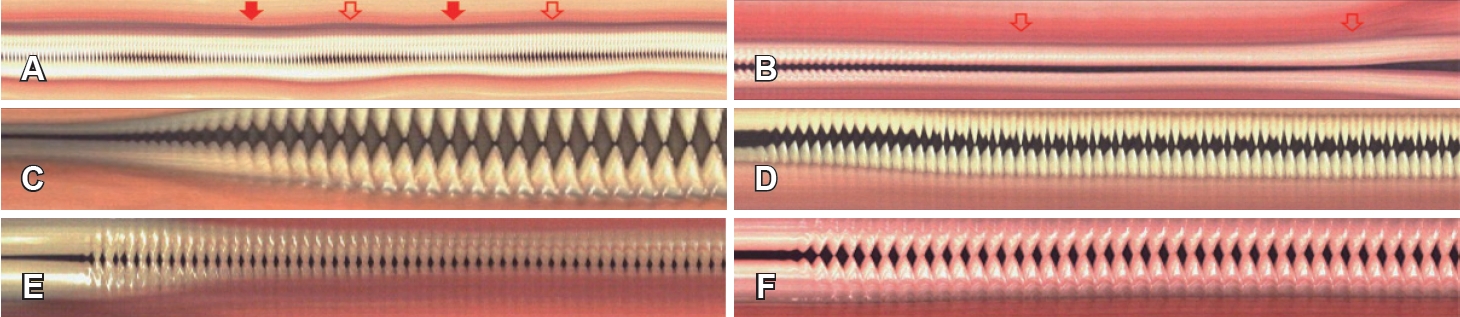

To facilitate diagnostic interpretation, representative multiline kymographic characteristics of functional dysphonia are illustrated in Fig. 2. These images presented as reference materials to the raters prior to independent evaluation.

From each HSV recording, three sets of multi-line DKG materials were generated: 1) DKG without voice playback, 2) DKG with non-synchronized voice playback, and 3) DKG with synchronized voice playback. Except for the presence or absence of audio, all visual parameters and display settings were identical across the three conditions. For diagnostic assessment, raters were instructed to provide the diagnostic label in an open-ended manner to avoid bias and to reflect real- world clinical decision-making.

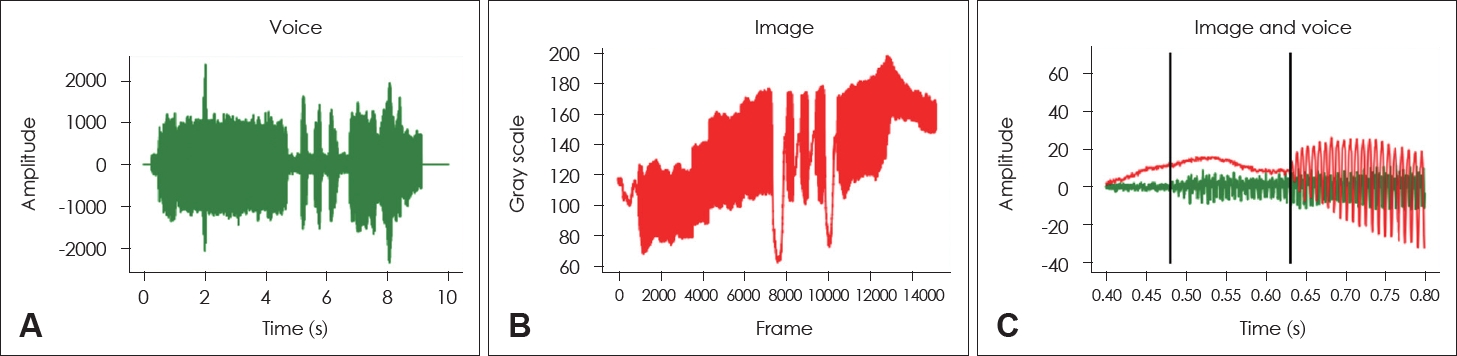

Implementation of gray scale glottographic application for alignment between the HSV images and voice signalsWhen running automated DKG, the start times of the multiline DKG image and the voice signal are different. To determine the starting point of the multi-line DKG image, we developed whole glottis gray scale glottography to measure the brightness between the opening and closing of the glottis. The language of the developed software was Python 3.9. The start time was adjusted by comparing the gray scale glottographic waveform with the sound waveform. By aligning the starting points as shown in Fig. 3, the difference between the starting points of the multi-line DKG images and the voice signal could be analyzed up to 0.001 s. As seen in Fig. 3C, it was confirmed that the starting point of the multi-line DKG images was delayed by about 146 ms compared to the voice signal. The discrepancy in start time occurred because during HSV shooting, audio recording started when the foot switch was pressed, and HSV recording started when the foot switch was released.

Computer systemThe examination was conducted on a computer running the Windows operating system equipped with an Intel Core i7 processor, 32 GB of RAM, and a USB 3.0 port.

Data analysisThis study compared the diagnostic accuracy of DKG, DKG with non-synchronized voice playback, and DKG with synchronized voice playback for voice disorders. Three raters independently interpreted each condition, allowing for the calculation of diagnostic accuracy for each condition. Intra-rater reliability was assessed using the same case by three raters at 3-week intervals, and was analyzed using Cohen’s kappa. In terms of inter-rater reliability, three raters evaluated the same case and confirmed the degree of reliability between raters. Fleiss’ kappa was used to assess reliability. The raters were two otolaryngologists and one speech and language pathologist, with 45, 25, and 27 years of work experience, respectively.

Statistical analysisA Z-test was performed to determine the differences in diagnostic accuracy between the methods (Table 2). Statistical analyses of Cohen’s kappa, Fleiss’ kappa, and the Z-test were performed using SPSS software (version 22.0; IBM Corp.).

ResultsIntra-rater reliabilityIntra-rater reliability was calculated using Cohen’s kappa based on test-retest results obtained at 3-week intervals. For Rater 1, the coefficients were 0.719 for DKG, 0.720 for DKG with non-synchronized playback, and 0.832 for DKG with synchronized playback, showing a statistically significant improvement under the synchronized condition. Rater 2 recorded coefficients of 0.722, 0.696, and 0.856, respectively, also indicating a significant advantage for the synchronized condition. Rater 3 obtained coefficients of 0.832, 0.856, and 0.759, with significant differences across conditions, although the direction of change varied. Overall, these results suggest substantial intra-rater reliability (Table 3).

Inter-rater reliabilityInter-rater reliability was assessed using Fleiss’ kappa. The coefficients were 0.650 for DKG, 0.624 for DKG with non-synchronized playback, and 0.658 for DKG with synchronized playback, indicating moderate to substantial agreement across raters (Table 4).

Diagnostic accuracy across three conditionsAs shown in Table 2, diagnostic accuracy was highest for DKG with synchronized voice playback (76.1%), followed by DKG with non-synchronized playback (58.1%) and conventional DKG (41.5%). Pairwise comparisons showed that synchronized playback significantly outperformed both conventional (p=0.0319) and non-synchronized DKG (p=0.0001), while non-synchronized playback also exceeded conventional DKG (p=0.0425).

Notably, diagnostic accuracy under the synchronized condition was almost twice that of conventional DKG, underscoring the added value of auditory feedback in complementing visual analysis. Improvements were particularly evident in functional disorders such as spasmodic dysphonia and tremor, where irregular closure or periodic fluctuations could be more reliably identified when the acoustic breaks were simultaneously heard.

Reliability analyses further supported these findings (Tables 3 and 4). For intra-rater reliability, Cohen’s kappa coefficients ranged from 0.696 to 0.856, with the highest values under the synchronized condition (0.832, 0.856, and 0.759 for Raters 1-3, respectively). These results suggest that synchronized playback reduces subjective variability and enhances consistency in interpretation, as intra-rater agreement reached the “almost perfect” range. Inter-rater reliability assessed with Fleiss’ kappa was moderate to substantial across conditions (0.650 for conventional DKG, 0.624 for non-synchronized playback, and 0.658 for synchronized playback).

In addition, representative multi-line DKG patterns were observed for different disorders (Supplementary Videos 2-7). In presbyphonia, the left and right vocal folds vibrated in phase, but glottic insufficiency due to vocal muscle atrophy was apparent. Tremor cases exhibited irregular vibration patterns with fluctuations in amplitude and timing, sometimes failing to complete opening or closure. Spasmodic dysphonia showed intermittent spasms leading to irregular amplitude and closure timing, with asymmetry between upper/lower and left/right folds. In vocal fold paralysis, marked phase differences, asymmetric mucosal waves, and incomplete closure were observed. Reinke’s edema resulted in thickened folds with incomplete or slow closure and reduced amplitude, usually symmetrical but sometimes slightly asymmetric depending on severity. Vocal fold cysts caused phase asymmetry and reduced amplitude on the affected side, along with disrupted mucosal waves. These representative findings demonstrate that multi-line DKG provides visual cues that support the diagnosis of various voice disorders.

DiscussionLaryngeal diseases can be divided into visible and nonvisible lesions. Visible lesions include inflammatory, benign, and malignant conditions, while non-visible lesions comprise functional voice disorders and neurologic dysphonia. Morphological tools such as laryngoscopy, LVS, and HSV are useful for visible lesions, but invisible lesions require functional imaging for accurate diagnosis.

Although HSV does not provide acoustic feedback, it remains the most powerful visual diagnostic tool, offering superior qualitative and quantitative evaluation compared with LVS [19]. Several HSV-based methods have been developed, including DKG and kymographic edge detection, which enable objective assessment of left-right vocal fold symmetry and vibratory patterns. DKG further quantifies amplitude, phase asymmetry, and parameters such as OQ, CQ, and SQ, similar to glottographic measures [19]. Patel, et al. [20] identified five kinematic parameters—amplitude periodicity, time periodicity, phase asymmetry, spatial symmetry, and glottal gap index—highlighting age-related differences.

Simulated stroboscopy, derived from HSV, was first reported in 2005 [21,22], providing more reliable assessment than LVS with acoustic feedback. Laryngeal kymography, originally based on photokymography [23] and strip kymography [24], can be classified as VKG or DKG. Line-scanning VKG directly captures high-speed images (>7810 lines/s) [18,25] with smaller data size and audio synchronization, but it is limited to a single scan line and prone to motion artifacts. In contrast, 2D VKG [26] and 2D DKG [15] enable real-time voice-synchronized visualization, but suffer from severe inter-cycle variability, reducing their reliability compared with DKG [27].

Among the various laryngeal kymographies, multi-line DKG does not provide acoustic feedback. To overcome this limitation, we implemented an automated system that enables synchronized voice playback, allowing clinicians to assess vocal fold vibration with both visual and auditory cues.

Precise synchronization between the voice signal and HSV images is critical. In this study, we applied gray scale glottography to align the audio and image data, ensuring accurate temporal matching [28].

In this study, synchronized voice playback significantly improved the diagnostic accuracy of DKG compared with conventional and non-synchronized methods, underscoring its potential clinical value. However, diagnostic accuracy remained below 80%, indicating that multi-line DKG alone is insufficient for comprehensive assessment. Greater accuracy is likely when it is used in combination with other modalities such as LVS and HSV, particularly in functional voice disorders.

Beyond diagnostic accuracy, its clinical implications are also noteworthy. Synchronized voice playback may be particularly valuable in clinical decision-making, as it enables clinicians to directly relate visualized vibratory patterns to perceptual voice quality. This facilitates collaboration between otolaryngologists and speech-language pathologists, who often rely on both auditory and visual cues to establish a diagnosis and plan therapy. For example, the ability to simultaneously observe irregular closure patterns and hear corresponding acoustic breaks may improve the accuracy of diagnosing spasmodic dysphonia, or help differentiate muscle tension dysphonia from neurologic dysphonia.

Despite these promising findings, some limitations should be acknowledged. Because the study cohort included both functional/neurologic and morphological lesions, heterogeneity may have influenced diagnostic accuracy. Future studies should stratify patients by pathology type to allow more disease-specific interpretation.

Kymography can quantify the cycle-to-cycle movement of the entire vocal fold over time, including the movement of each vocal fold sampled in a single line or multiple lines. Therefore, this method is very useful for visually assessing the asymmetry of the left and right vocal folds, and visually confirming vocal fold vibration in various vibration characteristics of healthy and disordered voices. Being able to listen to the voice simultaneously when analyzing the DKG also aids in the evaluation of vocal fold vibration and could be helpful in diagnosis.

In conclusion, DKG with synchronized voice playback is a useful tool for diagnosing patients with voice disorders. It complements vocal fold vibration evaluation and supports diagnosis by making it possible to listen to voices simultaneously during DKG analysis.

Supplementary MaterialsThe Supplement is available with this article at https://doi.org/10.3342/kjorl-hns.2025.00409.

NotesAuthor Contribution Conceptualization: Dong-Won Lim, Jin-Choon Lee. Data curation: Seon-Jong Kim, Soon-Bok Kwon. Formal analysis: Dong-Won Lim, Hee-June Park, Soon-Bok Kwon. Investigation: Minhyung Lee, Eui-Suk Sung. Methodology: Dong-Won Lim, Hee-June Park. Software: Seon-Jong Kim, Min-Kyu Kim, Duck-Hoon Kang. Validation: Byung-Joo Lee, Min-Kyu Kim. Visualization: Seon-Jong Kim, Jaewon Kim, Dae-Ik Jang. Writing—original draft: Dong- Won Lim, Hee-June Park, Writing—review & editing: Jin-Choon Lee, Byung-Joo Lee. Fig. 1.The graphic user interface of automated digital kymography (DKG) with synchronized voice playback. A: Navigation laryngoscopic image. B: Ten lines of DKG.

Fig. 2.Kymographic characteristics of various voice disorders. A: Essential tremor. Red and uncolored arrows indicate the portions of the curve corresponding to vocal fold vibration. B: Spasmodic dysphonia. The arrow indicates the sustained period at the end of phonation when the vocal folds remain approximated without residual mucosal wave. C: Presbyphonia. D: Left vocal fold paralysis. E: Muscle tension dysphonia. F: Normal.

Fig. 3.Synchronization of voice signal (A) and gray scale glottographic signal converted from high-speed videolaryngoscopy (HSV) (B). A: Voice signal. B: Gray scale glottographic signal converted from HSV. C: Alignment of the voice and glottographic signal before calibration. The glottographic signal is delayed by 146 ms compared to the voice signal.

Table 1.Details of the participants (n=102) Table 2.Number of correct answers for each method in the voice disorders (n=102)

Table 3.Intra-rater reliability (Cohen’s Kappa coefficient)

REFERENCES1. Boone DR, McFarlane SC, Von Berg SL, Zraick RI. The voice and voice therapy. 9th ed. Boston: Pearson;2014.

2. Patel R, Dailey S, Bless D. Comparison of high-speed digital imaging with stroboscopy for laryngeal imaging of glottal disorders. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2008;117(6):413-24.

3. Döllinger M, Kunduk M, Kaltenbacher M, Vondenhoff S, Ziethe A, Eysholdt U, et al. Analysis of vocal fold function from acoustic data simultaneously recorded with high-speed endoscopy. J Voice 2012;26(6):726-33.

4. Krausert CR, Olszewski AE, Taylor LN, McMurray JS, Dailey SH, Jiang JJ. Mucosal wave measurement and visualization techniques. J Voice 2011;25(4):395-405.

5. Hirose H. High-speed digital imaging of vocal fold vibration. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 1988;458:151-3.

6. Svec JG, Schutte HK. Videokymography: high-speed line scanning of vocal fold vibration. J Voice 1996;10(2):201-5.

7. Olthoff A, Woywod C, Kruse E. Stroboscopy versus high-speed glottography: a comparative study. Laryngoscope 2007;117(6):1123-6.

8. Deliyski DD, Petrushev PP, Bonilha HS, Gerlach TT, Martin-Harris B, Hillman RE. Clinical implementation of laryngeal highspeed videoendoscopy: challenges and evolution. Folia Phoniatr Logop 2008;60(1):33-44.

9. Wittenberg T. Automatic motion extraction from laryngeal kymograms. In: Wittenberg T, Mergell P, Tigges M, Eysholdt U, editors. Advances in quantitative laryngoscopy. Göttingen: Verlag Abteilung Phoniatrie;1997. p.21-8.

10. Huang CC, Leu YS, Kuo CF, Chu WL, Chu YH, Wu HC. Automatic recognizing of vocal fold disorders from glottis images. Proc Inst Mech Eng H 2014;228(9):952-61.

11. Lohscheller J, Svec JG, Döllinger M. Vocal fold vibration amplitude, open quotient, speed quotient and their variability along glottal length: kymographic data from normal subjects. Logoped Phoniatr Vocol 2013;38(4):182-92.

12. Chen W, Woo P, Murry T. Spectral analysis of digital kymography in normal adult vocal fold vibration. J Voice 2014;28(3):356-61.

13. Yamauchi A, Imagawa H, Sakakibara K, Yokonishi H, Nito T, Yamasoba T, et al. Phase difference of vocally healthy subjects in high-speed digital imaging analyzed with laryngotopography. J Voice 2013;27(1):39-45.

14. Lohscheller J, Eysholdt U, Toy H, Dollinger M. Phonovibrography: mapping high-speed movies of vocal fold vibrations into 2-D diagrams for visualizing and analyzing the underlying laryngeal dynamics. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2008;27(3):300-9.

15. Kang DH, Wang SG, Park HJ, Lee JC, Jeon GR, Choi IS, et al. Real-time simultaneous DKG and 2D DKG using high-speed digital camera. J Voice 2017;31(2):247.e1-7.

16. Chodara AM, Krausert CR, Jiang JJ. Kymographic characterization of vibration in human vocal folds with nodules and polyps. Laryngoscope 2012;122(1):58-65.

17. Qiu Q, Schutte HK, Gu L, Yu Q. An automatic method to quantify the vibration properties of human vocal folds via videokymography. Folia Phoniatr Logop 2003;55(3):128-36.

18. Tigges M, Wittenberg T, Mergell P, Eysholdt U. Imaging of vocal fold vibration by digital multi-plane kymography. Comput Med Imaging Graph 1999;23(6):323-30.

19. Maryn Y, Verguts M, Demarsin H, van Dinther J, Gomez P, Schlegel P, et al. Intersegmenter variability in high-speed laryngoscopy-based glottal area waveform measures. Laryngoscope 2020;130(11):E654-61.

20. Patel R, Dubrovskiy D, Döllinger M. Characterizing vibratory kinematics in children and adults with high-speed digital imaging. J Speech Lang Hear Res 2014;57(2):S674-86.

21. Powell ME, Deliyski DD, Hillman RE, Zeitels SM, Burns JA, Mehta DD. Comparison of videostroboscopy to stroboscopy derived from high-speed videoendoscopy for evaluating patients with vocal fold mass lesions. Am J Speech Lang Pathol 2016;25(4):576-89.

22. Deliyski D, Shaw H, Martin‑Harris B, Gerlach T. Facilitative playback techniques for laryngeal assessment via high‑speed videoendoscopy. Paper presented at: 34th Annual Symposium: Care of the Professional Voice; 2005 Jun 1-5; Philadelphia, PA, USA;2005.

23. Gall V, Gall D, Hanson J. [Laryngeal photokymography]. Arch Klin Exp Ohren Nasen Kehlkopfheilkd 1971;200(1):34-41, German.

25. Svec JG, Sram F, Schutte HK. Videokymography in voice disorders: what to look for? Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2007;116(3):172-80.

26. Wang SG, Lee BJ, Lee JC, Lim YS, Park YM, Park HJ, et al. Development of two-dimensional scanning videokymography for analysis of vocal fold vibration. J Korean Soc Laryngol Phoniatr Logop 2013;24(2):107-11.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|